How Might a Trump Victory Affect the EU?

How Might a Trump Victory Affect the EU?

Teodor Nedev // 22 October 2024

The US Presidential election is only 2 weeks away and the campaigns of the main candidates are in full swing. Given Biden’s poor performance in the first presidential debate, internal party pressure on him to step down from the race, and the assassination attempt on Trump – who is leading in most recent polls – the Republicans seem to have a strong chance. A Trump victory would present two main challenges for the EU. First, Trump and the Republican Party’s protectionist tendencies could result in a more aggressive trade policy towards Europe. Second, the Trump administration may show little interest in maintaining US support for Ukraine or playing a major role in European defence generally. With such possible developments on the horizon, it is essential to consider the potential economic implications of a second Trump term for the EU.

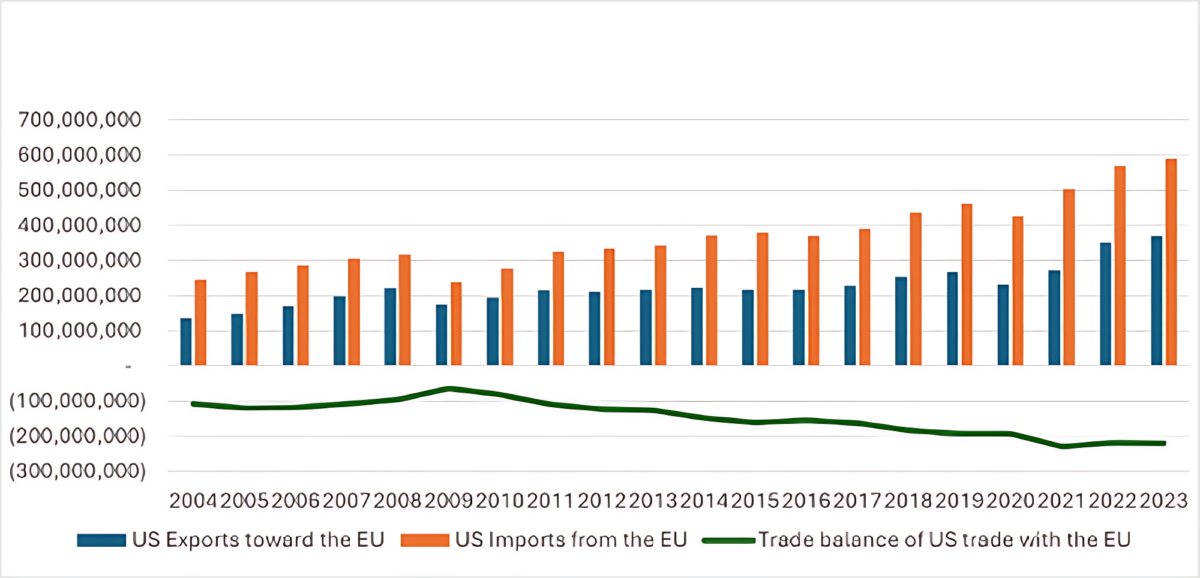

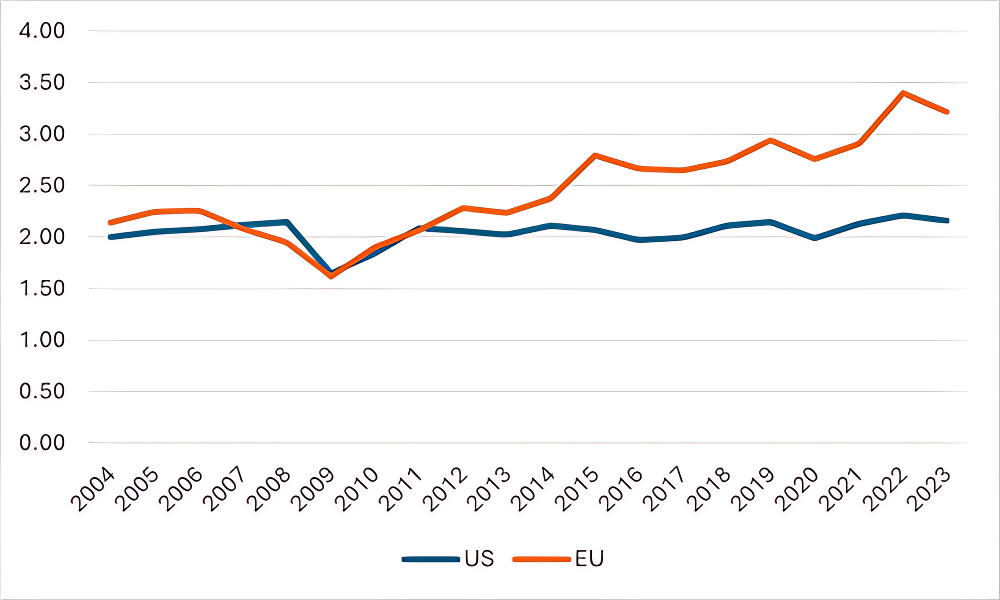

Although the Republican campaign has yet to outline its vision for US–EU trade relations in detail, past actions provide some clues. Trump and his team have indicated plans to introduce a 10 per cent tariff on all US imports, and a 60 per cent tariff on goods from China. Currently, the average tariffs between the two blocs are below 3 per cent, and the US trade deficit with the EU stood at $220 billion in 2023, making the EU a net exporter to the US market. Trump’s team prioritises balancing foreign trade, and views higher tariffs as a primary tool to achieve this, as evidenced during his first term.

Figure 1. Trade between the US and the EU: Imports, exports, and trade balance (in $)

For example, in 2018, the US imposed higher tariffs on steel and aluminium imports, 25 per cent and 10 per cent, respectively, from Europe. In 2019, it imposed additional tariffs on $7.5 billion worth of European goods in response to the EU subsidies for Airbus – a move sanctioned by the World Trade Organization (WTO). Both the Trump and Biden administrations have also threatened further tariffs on European goods due to the EU’s attempts to tax digital services provided by American tech companies. The EU did not sit idle during these disputes: when the US increased tariffs on European steel and aluminium, the EU retaliated with tariffs on various American products such as denim, whiskey, and motorcycles. In 2020, the WTO allowed the EU to impose tariffs on $4 billion worth of American goods, citing the US subsidies for Boeing.

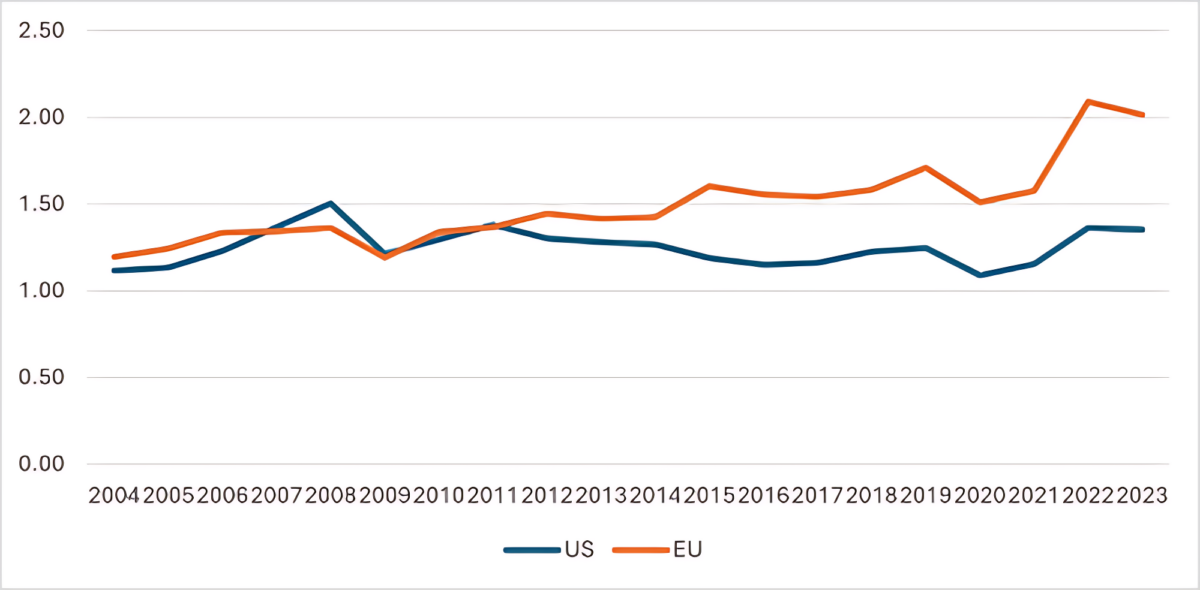

Most of these tariffs were eventually lifted after the two sides reached compromises. However, a second Trump administration could bring a shift. His proposed universal 10 per cent import tax appears to be a commitment to a firmer policy compared to the sporadic tariffs of his first term. Given the Republicans’ focus on narrowing the trade deficit, it is uncertain how the EU might respond or whether it could negotiate exemptions. This scenario would likely have a greater impact on the EU than the US, as trade between the two blocs constitutes a larger share of Europe’s GDP compared to America’s.

Figure 2. Imports to the US from the EU (% of GDP for both blocs)

Figure 3. US Exports to the EU (% of GDP for both blocs)

There are also indirect risks to consider. A broad increase in US import tariffs could limit global access to the American market, intensifying competition for European exporters. This would particularly disadvantage relatively high-cost European goods in price-sensitive markets. Moreover, if the EU responded by raising its tariffs, European consumers could face higher prices and fewer product choices. Another potential retaliatory measure could involve additional taxes or regulatory barriers on the US tech firms operating in Europe. Overall, such developments could slow global trade and have a significant impact on the EU’s largely export-oriented economy.

The graver concern: Defence

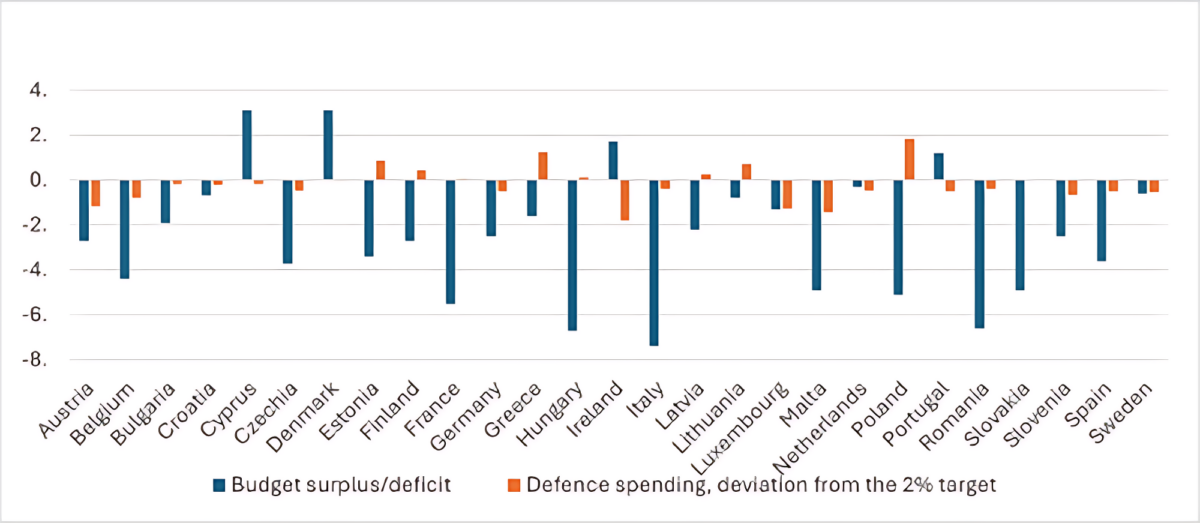

However, the more serious risk for the EU lies in the realm of defence rather than trade. Trump and many other Republicans have repeatedly argued that the US should reduce its military support for Ukraine and push Europe to take on a more significant role within NATO. While the exact direction of a more isolationist US defence policy in a second Trump term is hard to predict, it is likely that European countries would need to increase their defence spending. This is particularly relevant given Trump’s recent comments suggesting that he would not extend military support to NATO members who fail to meet the 2 per cent GDP defence spending target. As of 2023, most European NATO members are still below this threshold, although projections for 2024 indicate that over two-thirds may surpass the 2 per cent mark.

If European nations do commit to sustainably increasing their defence budgets, this could place additional strain on already overstretched public finances, especially since the 2 per cent threshold is now being seen as insufficient given regional security risks. Europe remains fiscally constrained – deficits and high debt levels are the norm in many EU countries, which makes it difficult to finance increased defence spending. This could force EU states to make tough choices about trade-offs between defence and other priorities, such as infrastructure, education, or social policies. Allocating more funds to defence would only be the first step: many European NATO members face significant personnel shortages – in fields such as soldiers, medics, and technicians – as well as production capacity gaps for weapons and munitions, which will require strategic investments to address.

Figure 4. Budget balances and defence expenditures relative to the 2% of GDP target for EU countries (% of GDP)

A third significant issue is that the perceived threat in the region could escalate sharply if the US adopts a more passive stance on European security, particularly, in reducing its commitment to supporting Ukraine. Economies thrive on stability, and it is unrealistic to expect steady growth in investment and consumer confidence if there is an increased risk of conflict in or around Europe. As a result, it falls on European nations to take proactive steps to mitigate these risks by developing a clear and robust defence policy, regardless of the reliability and predictability of their international partners.

This blog was originally published by IME in Bulgarian.

EPICENTER publications and contributions from our member think tanks are designed to promote the discussion of economic issues and the role of markets in solving economic and social problems. As with all EPICENTER publications, the views expressed here are those of the author and not EPICENTER or its member think tanks (which have no corporate view).