Norwegian Sugar Tax Sends Sweet-lovers Over Border to Sweden

Let's Stop Europe Falling Behind

Christopher Snowdon // 28 November 2019

It seems unfair to call it a sweet shop. In the shopping centre north of Charlottenberg in south-western Sweden, barely four miles from Norway and less than 90 minutes’ drive from Oslo, is a candy superstore.

Arrayed across 3,500 sq metres of floor space – half a football pitch – are aisle upon aisle of sugary treats, more than 4,000 products in all, from sour strawberries, liquorice laces and fruity gumballs to red rockets, Lion bars, M&Ms, Milky Ways and Oreos.

One of maybe 30 similar confectionery and soft drink stores lining the Swedish side of the border from south to far north, it is, said Matts Idbratt, operations manager for Gottebiten – which runs half of them – “the biggest sweet shop in the world. We think”.

Between them, those stores turn over about SEK2bn (£160m) a year – and they exist solely because the price tags on the pick’n’mix bags, snack bars, chocolate boxes and soft drinks they sell are, on average, less than half those in neighbouring Norway.

“It’s crazy,” said Eirik Bergland, a 39-year-old laboratory technician from the Oslo suburb of Bjerke. With three children under 12, he has made three cross-border shopping trips this year – although not just for sweets, he stressed.

“A lot of products are cheaper in Sweden than in Norway,” Bergland said. “Alcohol, tobacco, plenty of stuff. Cross-border shopping has happened for decades. But candy and soft drinks are a lot cheaper. A whole, whole lot cheaper.”

Norway has had a tax on sugary products since 1922. The Guardian says it was introduced ‘to raise revenue for the state, rather than improve the health of the nation’ as if this makes it any different from modern sugar taxes.

In January last year, the tax on chocolate and confectionery went up by 83% to the equivalent of £3.12 per kilo. The tax on fizzy drinks – including zero-sugar drinks – works out at about 43p a litre.

The result was predictable…

The tax increase had “quite an impact on our sales”, said Idbratt, whose giant sweet emporium is part of a booming cross-border trade that earned Swedish businesses – some owned by Norwegian investors – SEK16.6bn (£1.3bn) last year, 10% more than in 2017.

Idbratt said Gottebiten, founded by three entrepreneurial brothers in 1997, had “seen more customers, and existing customers are buying more”. Norwegian shoppers made 9.2m trips across the border last year, according to Statistics Norway.

It’s all very reminiscent of Denmark’s fat tax fiasco.

Still, there is no doubt that Norwegians have cut down on sugar, as another Guardian article reported last week:

“Norwegians are eating less sugar than at any time in the last 44 years, the health directorate in Oslo has said, announcing that annual consumption per person had fallen by more than 1kg a year since 2000. […]

The directorate’s annual report on the Norwegian diet said that average annual consumption of sugar had plummeted from 43kg to 24kg per person between 2000 and 2018 – including a 27% reduction in the past decade – to a level lower than that recorded in 1975.”

It’s not clear if these figures take account of cross-border shopping, but it is a remarkable drop either way. And so, naturally, rates of obesity have fallen commensurately, right?

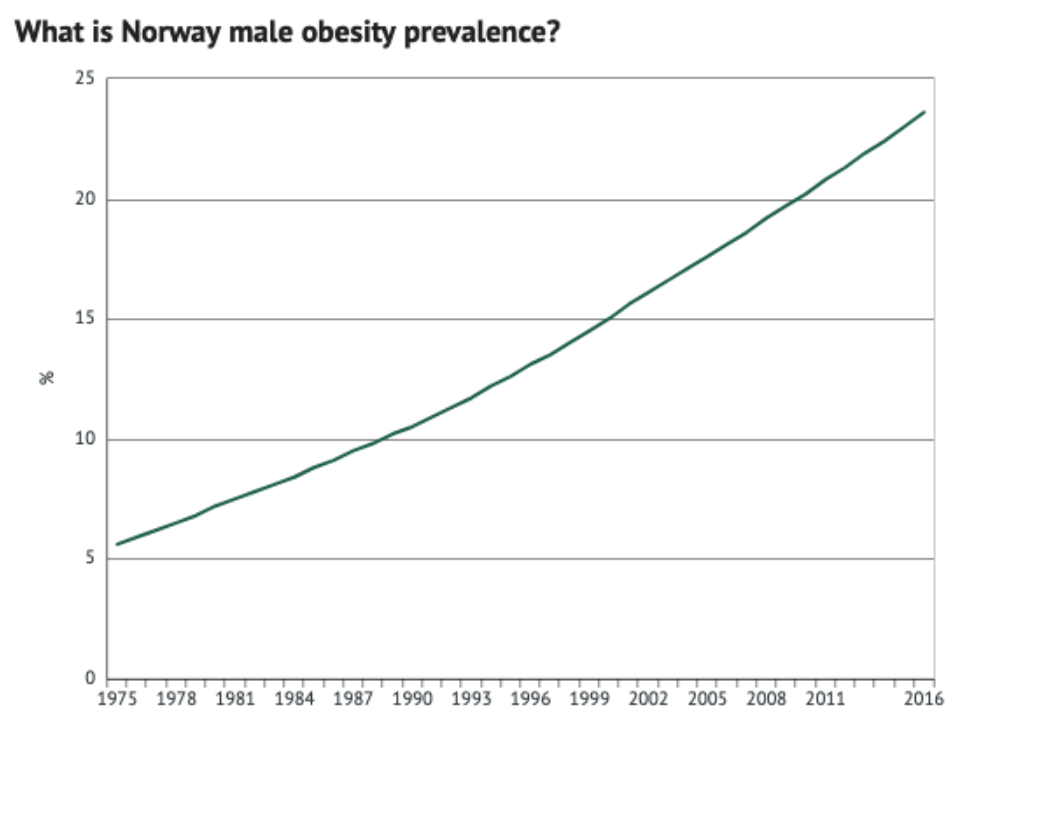

Wrong. According to the WHO, Norway has an obesity rate of 23.1 per cent, higher than Sweden’s 20.6 per cent and – for that matter – higher than Finland’s 22.2 per cent and Denmark’s 19.7 per cent.

Moreover, the record shows that Norway’s obesity rate has increased at a remarkably steady rate for many years, unaffected by changes in taxes or sugar consumption.

The picture is similar in Britain where sugar consumption has fallen by around a fifth since the 1960s – although campaigners are reluctant to admit this – while obesity has risen.

Maybe – just maybe – sugar isn’t the culprit and crude ‘public health’ policies based on dogma rather than facts don’t work?

Still, good news for Sweden’s border town confectionery industry.

EPICENTER publications and contributions from our member think tanks are designed to promote the discussion of economic issues and the role of markets in solving economic and social problems. As with all EPICENTER publications, the views expressed here are those of the author and not EPICENTER or its member think tanks (which have no corporate view).